Most DMs have a couple of funny dice and a couple of weird houserules to go with them. This is a tradition that goes back to Gary Gygax. In the First Edition DMG, he says,

The author has a d6 with the following faces: SPADE, CLUB, CLUB, DIAMOND, DIAMOND, HEART. If, during an encounter, players meet a character whose reaction is uncertain, the card suit die is rolled in conjunction with 3d6. Black suits mean dislike, with the SPADE equalling hate, while red equals like, the HEART being great favor. The 3d6 give a bell-shaped probability curve of 3-18, with 9-12 being the mean spread. SPADE 18 means absolute and unchangeable hate, while HEART 18 indicates the opposite. CLUBS or DIAMONDS can be altered by discourse, rewards, etc. Thus, CLUBS 12 could possibly be altered to CLUBS 3 by offer of a tribute or favor, CLUBS 3 changed to DIAMONDS 3 by a gift, etc.

I’ve read the DMG a couple of times and I didn’t notice that passage till recently. The dice sound cool – similar to crown and anchor dice but better because they have a sort of bell curve built in, with some suits more common than others. (For that reason, they seem like they’d be pretty useless for most card-game purposes.) I haven’t found these dice in an eBay search, but I’ll keep looking. Funny dice like these – dice with no official game rules attached – beg to be used, and so they stretch the fabric of the rules. The big tent of D&D becomes just a tiny bit bigger to accommodate them.

I’ve read the DMG a couple of times and I didn’t notice that passage till recently. The dice sound cool – similar to crown and anchor dice but better because they have a sort of bell curve built in, with some suits more common than others. (For that reason, they seem like they’d be pretty useless for most card-game purposes.) I haven’t found these dice in an eBay search, but I’ll keep looking. Funny dice like these – dice with no official game rules attached – beg to be used, and so they stretch the fabric of the rules. The big tent of D&D becomes just a tiny bit bigger to accommodate them.

I already have a couple of my own funny dice and their accompanying funny-dice rules.

The danger die: I have a red die with a skull and crossbones on one side. In random-monster, random-complication, or random-unfortunate-event situations, I hand it to a player and say “Roll the danger die. Roll anything you want but don’t roll the skull and crossbones.” Over the course of our recent Isle of Dread playthrough, the players have come to fear the danger die.

The danger die: I have a red die with a skull and crossbones on one side. In random-monster, random-complication, or random-unfortunate-event situations, I hand it to a player and say “Roll the danger die. Roll anything you want but don’t roll the skull and crossbones.” Over the course of our recent Isle of Dread playthrough, the players have come to fear the danger die.

The dragon die and the dinosaur die I have a d6 with a dragon on one face. When inside a dragon’s territory, I’d have a player roll the danger die and the dragon die for every random monster check. On various occasions, the dragon die resulted in either panicked flight from, or victorious conquest of, the legendary black dragon from the recent Legends and Lore column. I also have a d6 with a different dinosaur on each face, That saw occasional use on the Isle of Dread. Outside of the Isle, I have a feeling that the dragon die is going to get rolled a lot more.

The dragon die and the dinosaur die I have a d6 with a dragon on one face. When inside a dragon’s territory, I’d have a player roll the danger die and the dragon die for every random monster check. On various occasions, the dragon die resulted in either panicked flight from, or victorious conquest of, the legendary black dragon from the recent Legends and Lore column. I also have a d6 with a different dinosaur on each face, That saw occasional use on the Isle of Dread. Outside of the Isle, I have a feeling that the dragon die is going to get rolled a lot more.

My dice box is the tin for a peg game called “Yachting: An Exciting Game.” “Y:AEG” is almost worthless as a game, but it came with two cool dice: a d6 with a lighthouse on one side, and a d8 with the cardinal and intermediate directions: North, Northwest, etc. I use these dice all the time.

The weather die: I don’t always roll for random weather each day, but our Isle of Dread campaign featured a druid whose lightning storm spell was much more powerful in stormy weather. Every morning, he’d ask, “What’s the weather today?” and I’d hand him the weather die. (6 means an appropriate-for-climate storm, and the 1/lighthouse means calm and possibly fog.) The result was that there was a lot more weather in the game than I’m used to; and the characters spent a lot more time slogging through mud than they were probably used to. I liked the added layer of detail from checking the weather, and I like that the mechanics of the druid spell makes the weather relevant to one of the characters, and thus, the group.

The weather die: I don’t always roll for random weather each day, but our Isle of Dread campaign featured a druid whose lightning storm spell was much more powerful in stormy weather. Every morning, he’d ask, “What’s the weather today?” and I’d hand him the weather die. (6 means an appropriate-for-climate storm, and the 1/lighthouse means calm and possibly fog.) The result was that there was a lot more weather in the game than I’m used to; and the characters spent a lot more time slogging through mud than they were probably used to. I liked the added layer of detail from checking the weather, and I like that the mechanics of the druid spell makes the weather relevant to one of the characters, and thus, the group.

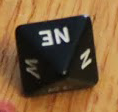

The direction die: A d8 direction die is built into 1e D&D game rules (both for wind speed and for “grenade-like missiles”). You’re supposed to use 1 for north, 2 for northeast, etc. It’s nice to have the directions right on the die. As a group, we don’t throw a ton of grenades, but we tend to play a lot of naval adventures, so this die gets used all the time.

The direction die: A d8 direction die is built into 1e D&D game rules (both for wind speed and for “grenade-like missiles”). You’re supposed to use 1 for north, 2 for northeast, etc. It’s nice to have the directions right on the die. As a group, we don’t throw a ton of grenades, but we tend to play a lot of naval adventures, so this die gets used all the time.

Little d6es: I don’t always have the energy to go digging for appropriate miniatures for every encounter. About half the dice in my dice box are from a colored assortment of mini d6es. They’re a great mini substitute, and the colors and pips are good for marking factions and hit points. The high point for the mini d6es was during our gonzo epic-level 4th Edition battle against Tiamat. Handfuls of white, black, red, green, and blue d6es each stood for dragons of the appropriate color.

Little d6es: I don’t always have the energy to go digging for appropriate miniatures for every encounter. About half the dice in my dice box are from a colored assortment of mini d6es. They’re a great mini substitute, and the colors and pips are good for marking factions and hit points. The high point for the mini d6es was during our gonzo epic-level 4th Edition battle against Tiamat. Handfuls of white, black, red, green, and blue d6es each stood for dragons of the appropriate color.

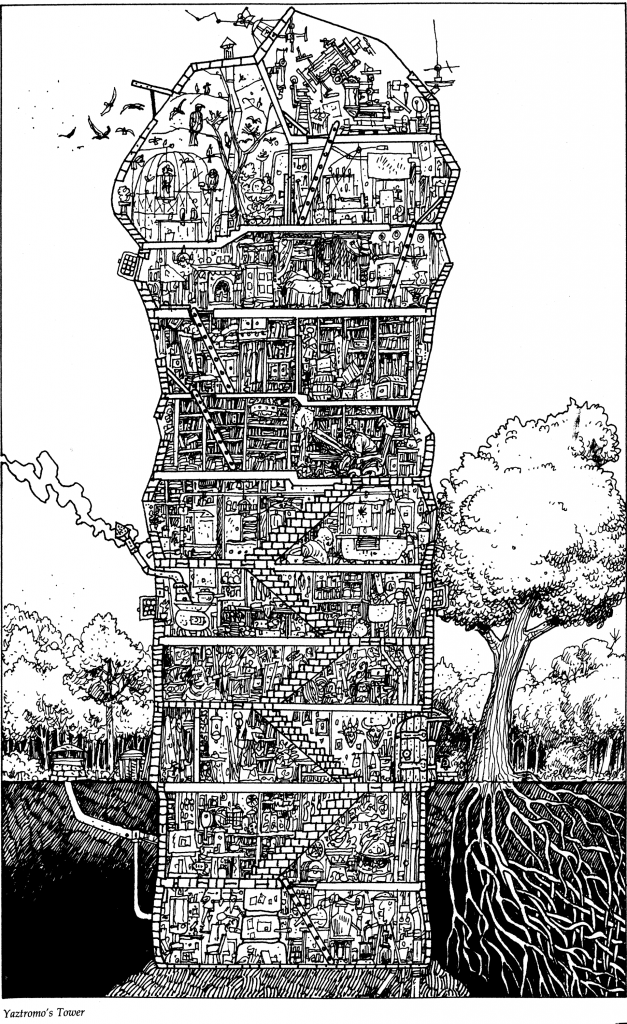

Other dice: I’ve got plenty of other weird dice still waiting for their opportunity to come into their own. I’ve occasionally used the pig die (when the PCs were searching for wild game, and as a stand-in mini for a particularly tough and fat evil cultist) but I haven’t found use for the unicorn, letter, month, or Tower of Gygax die yet. I’m gonna hold on to them all though. A funny die is a house-rule generator. I’m sure all these dice have a use. I just haven’t figured it out yet.

Other dice: I’ve got plenty of other weird dice still waiting for their opportunity to come into their own. I’ve occasionally used the pig die (when the PCs were searching for wild game, and as a stand-in mini for a particularly tough and fat evil cultist) but I haven’t found use for the unicorn, letter, month, or Tower of Gygax die yet. I’m gonna hold on to them all though. A funny die is a house-rule generator. I’m sure all these dice have a use. I just haven’t figured it out yet.