Last week we started work on the Mazes and Monsters combat system, figuring out HP and damage. That was the easy part: hit rolls are really the central feature of combat.

Let’s use RONA for this. As you may remember, using RONA, you roll a D12 and try to hit a target number. If you have an applicable trait, you roll 2d12 and take the highest number.

Wimpy monsters require an Easy Rona (a roll of 3 or more on an exploding d12); middle-range monsters Average (6) and tough or well-armored foes Hard (9).

Characters don’t necessarily get much better at hitting as they level. As soon as they get a trait that lets them roll 2d12 for their attack, they’re as good as they’ll ever be.

This is a departure from fantasy RPGs like D&D, which give the PCs (and monsters) steadily increasing hit chances as they level. Mazes and Monsters, on the other hand, provides steadily increasing damage; we don’t need to double-dip.

Armor

Armor in Mazes and Monsters is very limited! Iglacia the Fighter has listed among her possessions “armor”, “shield”, and “helmet”. No “leather”, “chain”, or “plate”; no armor+1. Just “Armor”.

Let’s say that hitting an unarmored character requires an Average success: in essence, you need to roll a 6 to hit them. We’ll give each of Armor, Helm, and Shield a +1 to that number, so a fully-armored character like Iglacia requires a 9 to hit: a Hard RONA.

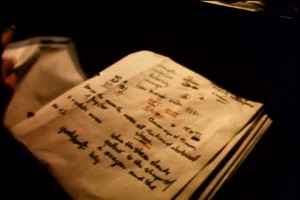

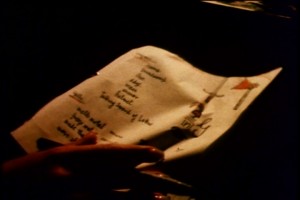

Is there anything on Iglacia’s character sheet to bear out this theory?

Well, there is a stat right below H.P. I can’t make out the acronym: it’s two letters, and its value is 10. If I had to guess, I’d say that the letters were “P.T.” or “T.P.” or “B.R.” or something like that. Since I can’t figure out what it is, I’m going to declare that it’s “P.R.”, “Protection RONA”. It’s 10, instead of 9, which gives Iglacia a better defense than we theorized! Maybe Armor grants +2 P.R. while the helm and shield grant +1 each.

Weapons

Iglacia has a couple of weapons on her character sheet: mace, axe, and the Talking Sword of Loghri. She must have had some reason for keeping her mace even after she got her Talking Sword of Logrhi. How are we going to differentiate these weapons?

I’m tempted to adopt the D&D3 solution of giving monsters resistances and weaknesses to bashing, piercing, or slashing weapons. We can extend that to spells, too: maze mummies are weak to fire, for instance.

Actually, given that the only type of armor is “armor”, the list of weapons in Mazes and Monsters probably isn’t very long. No footman’s mace or Bohemian earspoon here. Instead of dividing weapons into categories, we can just give monsters resistances to specific weapons.

While we’re here, let’s come up with the weapons list. It probably looks something like

sword

mace

axe

spear

dagger

bow

staff

Let’s handle monster weaknesses and resistances by adjusting the monster’s P.R. (Protection RONA): +3 for resistances and -3 for weaknesses. For instance:

Mystic Skeleton

PR: 6 (9 vs arrows, swords and daggers)

Maiming and Slaughter

We’ve already come up with a colorful Maiming table. We can now tie that to the RONA system. If you (or a monster) get a critical success (10 higher than the RONA target number) you can roll on the maiming table. If you happen to roll a double crit (20 higher than the RONA) let’s say you kill your target instantly. We’ll call that a slaughter because that’s the sort of term that probably would have distressed 80s parents.

Say, what are the odds of having a character get Slaughtered by a freak roll of the dice?

I tend to think that monsters always roll 1d12s: the extra d12 from Traits are one of the ways that players have an advantage over their environment. In order to Slaughter an unarmored character with a RONA of 6, a monster needs a 26. That means rolling 12 twice, and then rolling a 6 or higher. The odds of this are about 1 in 300.

How many times is a character attacked between level 1 and level 9? Well, earlier we decided that it takes 70 game sessions to get to level 9. Let’s conservatively guess that there are two combats per session. Unarmored characters try to stay out of the way, but they probably get attacked at least once per battle. Over 9 levels, that’s about 300 attacks: you’ve got an even chance of being Slaughtered before you get to level 10. Add to that the chances of death by HP depletion, traps, tricks, and Maze-related madness, and it’s obviously quite an accomplishment to make it to the level-10 cap.

Fumbling

If there’s a special chart for critical hits, there needs to be a chart for critical failures too. If you roll ten less than a target Protection RONA, you have to roll on the Fumble Chart.

Fumble Subtable

1: The character impales himself with his or another’s weapon. Character rolls damage on himself.

1: The character makes the same attack again, this time on an ally.

3: The character’s weapon or spell breaks.

4-5: The character’s weapon or spell flies across the room.

6-7: The character leaves himself open. One opponent may make a free attack.

8-9: The character falls down. He loses his next turn.

10-11: The character misses spectacularly. No other effect.

12: If there is another enemy in range, the character automatically hits that enemy.

On a double fumble (20 lower than the target’s P.R.) the character kills himself with his own weapon.

OK, our combat system is pretty solid. We maybe erred in basing it on the same mechanic as everything else in the game; to maintain fidelity to 80’s RPG style, we should have had it be a whole separate subsystem. But at least we jammed in a few unnecessary charts.

Next week we’ll finish off whatever odds and ends of rules we haven’t addressed yet. The Mazed condition springs to mind. Then, the week after: the official release of Mazes and Monsters 1st Edition, just in time for Christmas!

Edit: We won’t do that. Instead, next time: we’ll get mazed!