I don’t know if Gary Gygax’s players did a lot of planar adventures in the D&D Great Wheel (which I grade here), but I do know that they frequently traveled to other dimensions – in other words, alternate genres or game systems rather than parts of the Great Wheel cosmology – and some are mentioned in the OD&D and AD&D manuals and elsewhere.

Dave Arneson said, on a message board post, “Lost Worlds, parallel worlds, future worlds, mythical worlds, etc. All are a lot of fun. A good point made here is that the ‘new’ world must have many critters unique just to it. We had Ross Maker’s and Dave Wesely’s ‘Source Of The Nile World’ and MAR Barkers TEKUMEL world when we wanted to go there. It was a good change of pace and let me have someone else referee for a bit.”

How do these adventures in parallel dimensions stack up against the planes of the D&D cosmology?

BOOT HILL: Gary’s players sometimes jumped over to BOOT HILL, Gygax and Blume’s cowboy game, where they got to play with six-shooters. There’s lots of adventure tropes to be had in a western setting, so even though the idea of clerics at the OK Corral may not sound like D&D to you, it’s way more interesting than clerics at the Quasi-Elemental Plane of Mud.

BOOT HILL: Gary’s players sometimes jumped over to BOOT HILL, Gygax and Blume’s cowboy game, where they got to play with six-shooters. There’s lots of adventure tropes to be had in a western setting, so even though the idea of clerics at the OK Corral may not sound like D&D to you, it’s way more interesting than clerics at the Quasi-Elemental Plane of Mud.

The 1e DMG included rules for converting your characters over to the Boot Hill system. Gunfighters imported into AD&D only got 3d4 for Wisdom; a pistol does 1d8 damage. Grade: B

Metamorphosis Alpha: Gary and his players also journeyed to James M. Ward’s sci-fi game set on a space ship called the Starship Warden, which was apparently even more dangerous and chaotic than an old-school D&D dungeon. Check out the story here. Notice that the characters were teleported into the space ship, not to the uninhabited, hostile, and featureless void outside the space ship. That’s already better than half the Great Wheel planes.

Metamorphosis Alpha: Gary and his players also journeyed to James M. Ward’s sci-fi game set on a space ship called the Starship Warden, which was apparently even more dangerous and chaotic than an old-school D&D dungeon. Check out the story here. Notice that the characters were teleported into the space ship, not to the uninhabited, hostile, and featureless void outside the space ship. That’s already better than half the Great Wheel planes.

If you want to try this yourself, James Ward is selling the first edition of Metamorphosis Alpha on lulu for 15 bucks. Grade: A

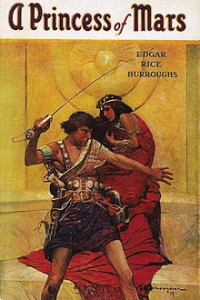

Mars: I love Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Mars books, and I’d love to play a D&D campaign there. The Mars books feature bizarre beasts, ruined cities, savage humanoid tribes, flying ships, and doomed points-of-light civilizations. Furthermore, the OD&D books already include wandering monster tables for the Martian people and monsters, so that’s, like, half the work done already. Grade: A+

Mars: I love Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Mars books, and I’d love to play a D&D campaign there. The Mars books feature bizarre beasts, ruined cities, savage humanoid tribes, flying ships, and doomed points-of-light civilizations. Furthermore, the OD&D books already include wandering monster tables for the Martian people and monsters, so that’s, like, half the work done already. Grade: A+

World War II: In this Strategic Review article, Gary Gygax described this great war-game skirmish between D&D monsters and a German patrol. It looks like fun, in a war game way, especially for WWII buffs. B

World War II: In this Strategic Review article, Gary Gygax described this great war-game skirmish between D&D monsters and a German patrol. It looks like fun, in a war game way, especially for WWII buffs. B

Overall grade of the alternate dimensions: A

My conclusion: arguments about the Great Wheel cosmology vs. the 4e planes are irrelevant to me, because both are worse than a stable of well-realized and varied fantasy worlds. Even a world with a strong theme, like Hoth or Dark Sun, is more interesting than a universe constructed of a single element and populated by soulless elementals and angels. Next time I introduce planar travel into a game, the gates will more likely go to the Wild West, Mars, or Gamma World than Limbo or the Plane of Fire.