This week, two exciting, unpublished TSR settings collided in my head to form a third setting.

setting 1: Jeff Grubb project

On the latest WOTC D&D podcast, Steve Winter talked about the great campaign-world books that came out of Second Edition D&D. He said that, for every kick-ass setting like Planescape or Al’Quadim, they had a bunch of ideas just as good – they just didn’t have time to print them all. Prompted, he described one of the settings that he’d never forgotten:

There’s one that always comes to mind: it was proposed by Jeff Grubb, and I forget what the name of it was, but the idea was, it was a world where there were all these mountain ranges, and all of civilization – the good part of civilization – has been driven up to the tops of these mountains, and then there’s a tremendously thick cloud layer, so wherever the sun shines is where good exists. Everything beneath the cloud layer has been overrun by evil. There are cloud ships that sail out from these mountain-top cities across the clouds, and the adventurers rappel down to the world where they go raiding the ruined cities that used to be down there, looking for gold, metal, and all the kinds of things that they don’t have in these mountaintop cities.

As Steve Winter says, that idea isn’t quite as fresh as it was in the late 80s (he’s seen elements in anime, and it reminds me of Final Fantasy) but I think it’s still an evocative and inspiring world. I’m ready to play it! But, since all we have is a podcast sound bite and not a campaign book, I’m left with a lot of questions: exactly what kind of evil lurks in the cloudy lowlands? What does the wilderness look like?

As Steve Winter says, that idea isn’t quite as fresh as it was in the late 80s (he’s seen elements in anime, and it reminds me of Final Fantasy) but I think it’s still an evocative and inspiring world. I’m ready to play it! But, since all we have is a podcast sound bite and not a campaign book, I’m left with a lot of questions: exactly what kind of evil lurks in the cloudy lowlands? What does the wilderness look like?

setting 2: “The Original D&D Setting”

Here’s the other great setting I read this week: The Original D&D Setting, a series of blog posts by Wayne Rossi. This teases out the weirdness that you get if you take the original OD&D books and play its assumptions to the hilt. Griffin-riding Arthurian knights wait inside sinister castles, swamps crawl with dinosaurs, there are Martian creatures in the desert, and undead shamble through cities.

Wayne Rossi provides a “campaign map” of this strange wild land: James Mishler’s version of the Outdoor Survival map that Gygax used for his wilderness adventures. When I took a close look at it, I noticed that three areas had little snow-capped peaks – presumably impassable. That’s when the Steve Winter idea crash-landed into the setting. What if those white-capped peaks aren’t covered with snow, but shining with sunlight? What if they’re the only safe places in the setting, and the PCs descend from the mountains to explore the misty lands of Wilderness Survival?

Wayne Rossi provides a “campaign map” of this strange wild land: James Mishler’s version of the Outdoor Survival map that Gygax used for his wilderness adventures. When I took a close look at it, I noticed that three areas had little snow-capped peaks – presumably impassable. That’s when the Steve Winter idea crash-landed into the setting. What if those white-capped peaks aren’t covered with snow, but shining with sunlight? What if they’re the only safe places in the setting, and the PCs descend from the mountains to explore the misty lands of Wilderness Survival?

A couple of nice things happen when we combine these settings:

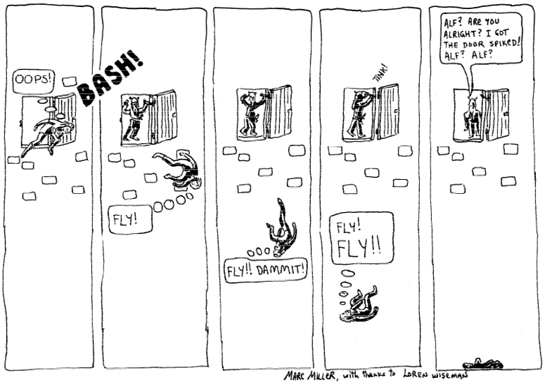

getting lost

Getting lost is a big deal in Wilderness Survival, and in the OD&D exploration rules. If you roll badly, you can end up wandering north when you think you’re going south. I’ve always wondered how getting lost by 180 degrees can happen on a sunny day, when you always know which ways East and West are. But suddenly, in this setting, it’s possible! Beneath the cloud cover, you can’t see the sun or the stars, and navigation is much harder than it is in a traditional outdoor adventure.

cities

Even if you’ve played a campaign on the classic Wilderness Survival map before, this setting inverts it. Usually, peaks are impassable and towns are your home base. Now, peaks are safe in a way that no valley village is. Cities will be places of horror: mockeries of safety.

In OD&D, in a city encounter, 50% of the time you roll on the “men” subtable and 50% of the time you roll on the “undead” subtable. Even in straight OD&D, there are way more undead in cities than we’re used to from later adventure settings. It really makes sense in this below-the-clouds horror setting, where, as Steve Winter says, the ruined cities are the primary dungeons. Since it’s always cloudy, you’re never safe from sun-fearing undead like vampires. Maybe the cities are filled with vampire lords who keep humans (the “men” encounters) as their cattle; maybe anyone who dies down here becomes undead, so cities are amoung the most dangerous places in the world; maybe the cities are straight-up dungeons ruled by necromancers and evil high priests (who together form 1/6 of the encounters on the “men” subtable).

Wayne points out that the arrangement of the cities is odd: there are five in a cross in the middle of the map, and the central one is in the forest. If we’re saying that ruined cities are the main dungeons of the settings, the central one, overgrown by eerie forest, is probably the scariest and most dangerous dungeon.

Wayne points out that the arrangement of the cities is odd: there are five in a cross in the middle of the map, and the central one is in the forest. If we’re saying that ruined cities are the main dungeons of the settings, the central one, overgrown by eerie forest, is probably the scariest and most dangerous dungeon.

castles

Most OD&D castle encounters, with wizards and clerics who enslave you and high-level fighters who challenge you, fit squarely into Steve Winter’s description of the wilderness as “overrun by evil.” While cities are the megadungeons of the settings, castles might be the bite-sized minidungeons that the players can try to clear in a single adventure.

Wayne Rossi makes the point that, according to the number of castles on the Wilderness Survival map and the castle-inhabitant charts, you’d expect three of the castles to be controlled by good clerics. I have my eye on the three castles in the mountain pass near the largest mountain peak area.

Wayne suggests that these good clerics are all part of one holy order dedicated to recapturing the land from evil. This makes sense to me. We can say that, while the surface of the world is nearly overrun with evil, there is one little area where a holy order has a foothold. This is the likely starting point of the PCs’ adventures: these castles control the only safe way to ascend to the mountain peaks. From the southernmost castle, it’s only 4 hexes to the closest city. That will undoubtedly be the first dungeon that the PCs tackle.

rivers

OK, there’s something I haven’t figured out. According to OD&D, rivers are just swarming with buccaneers and pirates. Who are they preying on? Each other?

Steve Winter said that cloud ships travel from mountain peak to mountain peak. Maybe the buccaneers and pirates are based on the river, but their ships can ascend to the clouds to attack cloud shipping. Maybe the pirates even have flying submarines.

Steve Winter said that cloud ships travel from mountain peak to mountain peak. Maybe the buccaneers and pirates are based on the river, but their ships can ascend to the clouds to attack cloud shipping. Maybe the pirates even have flying submarines.

That said, if pirates can fly, why do they spend so much time on the river? Maybe someone can solve this for me.

Another thing: there are a lot of flying monsters in the original OD&D encounter tables – dragons, griffins, chimerae. Can they threaten the mountain settlements and cloud ships, or are they confined to the lowlands?

This week I’ll try to delve more into the implications of this setting.