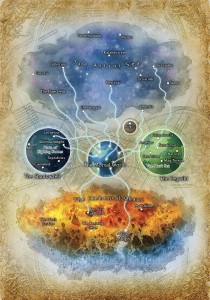

My rubric for judging the D&D planes of existence is “If you wandered into it by accident, could you have a good adventure there?” Since the 5e developers say they’re planning to return to the Great Wheel cosmology, let’s see how rich each Great Wheel plane is for adventuring possibilities.

My rubric for judging the D&D planes of existence is “If you wandered into it by accident, could you have a good adventure there?” Since the 5e developers say they’re planning to return to the Great Wheel cosmology, let’s see how rich each Great Wheel plane is for adventuring possibilities.

As a 3e player, I never adventured in the planes, so I’ll supplement my memory with the descriptions in the 3.5 Dungeon Master’s Guide.

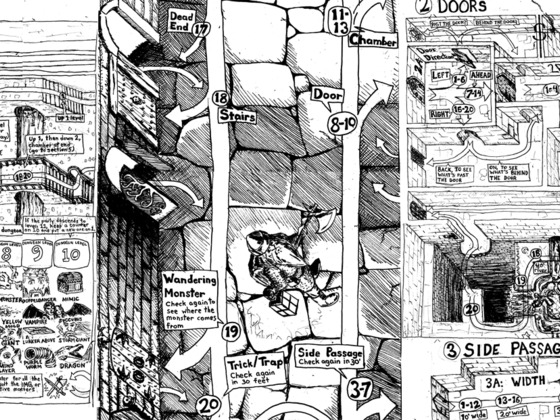

Ethereal Plane: A “collection of swirling mists and colorful fogs” through which you can see the Material Plane as through a window on the girl’s locker room. It’s primarily used to skip over walls in the dungeon, until the DM rules that every dungeon is in a no-ethereal-travel zone.

The Ethereal Plane is “mostly empty of structures and impediments.” The example location is “Misty Cemetery” and is identical to any misty cemetery. Boy, I can’t figure out why the 4e designers got rid of this. Grade: D

Plane of Shadow: “Landmarks from the Material Plane are recognizable in the Plane of Shadow, but they are twisted, warped things.” Like a Tim Burton movie! There are a lot of possibilities for horror adventures: it can contain the weird and unexplained, and terrifying versions of familiar places and people. here The 4e designers call this plane the Shadowfell, but it’s otherwise identical. Grade: A

The Astral Plane: Unlike the 4e Astral Sea, which is vivid with imagery of silver seas and floating islands, the Astral Plane is “a great, endless sphere of clear silvery sky”. So, a lot like the Plane of Air. Great. Can’t have too many featureless planes.

I guess you can have fun on a featureless plane, but if you do, it’s fun you brought with you.

The DMG’s example site for the Astral Plane is called, I kid you not, “Silver Sky”. So that’s what this plane has going on.

The only thing that saves the Astral Plane from an F is its interesting history featuring the Kabbalah and Madame Blatavsky. Grade: F+

Plane of Air: “The Plane of Air is an empty plane, consisting of sky above and sky below.” I guess you go here if you want to have a lot of encounters with birds. Grade: D

Plane of Earth: “An unwary and unprepared traveler may find himself entombed within this vast solidity of material and have his life crushed into nothingness.” Lots of adventures to be had here! All of the sample encounters are with earth elementals and xorn.

You know, this and the Plane of Air are really pointing up the fact that elements on their own are boring. They’re like eating only one color of m&m, but worse, because when you eat m&m,s you are rarely entombed within their vast solidity and crushed into nothingness. Grade: F

Plane of Fire: This is the elemental plane with the best visuals. However, I can’t see how you can adventure here. Even if you have fire resistance, there’s nothing to do but kill efreet, fire elementals, and salamanders.

The sample location is the City of Brass, which has definite possibilities. The Grand Sultan of All the Efreet rules from the Charcoal Throne! “It is said that within the great palace are wonders beyond belief and treasure beyond counting. But here also is found death for any uninvited guest who seeks to wrest even a single coin or bauble from the treasure rooms of the grand sultan.” Thus warned, shall ye enter? Grade: C

Plane of Water: The Plane of Water is at least traversible, unlike Earth and Fire, but I don’t see what benefit you get out of using it instead of the ocean. The ocean is already vast and deep and unknown, and a lot closer, and most players are still not interested in exploring it.

For maximum fun, I’d have a Plane of Water adventure include a mer-people kingdom beset by a navy of killer intelligent sharks, throw in a Cthulhu or two, and visit the ruined palace of a dead sea god wherein the players might be enslaved by emerald-eyed sirens. Then I’d take that adventure and put it back in the Material Plane ocean. Grade: D+

Quasi elemental planes: These come together at the borders of the elemental planes: like the border between the planes of Water and Earth is the Quasi-Elemental Plane of Mud. Gary Gygax came up with these for an early Dragon Magazine article, and I suspect he put about as much thought into it as I usually put into blog posts. No one has ever adventured in any of them. Grade: F

Negative Energy Plane: You die if you spend too long on the Negative Plane. There are no random encounters because it is “virtually devoid of life”. It seems to exist merely to provide an energy source for negative-energy spells. Grade: F

Positive Energy Plane: This plane “is akin to the Elemental Plane of Air with its wide-open nature.” Ooh, another featureless plane! But this one is different because you die if you spend time there. Like the Negative Energy Plane, it is “virtually devoid of creatures” and only exists to power spells.

The example location is the “Burst Cluster”, where there are occasional explosions. I guess that conveys a sense of place, as in “a place I want to leave.” Grade: F

The Outer Planes: From the Heroic Domains of Ysgard to the Windswept Depths of Pandemonium, the Outer Planes are the realms of the gods and demons, the homes of each alignment. There are 17 of them and they are too boring to tackle individually.

The good-aligned outer planes are generally pastoral and contain nice happy people who have no possible use for adventurers. Grade: D

The neutral-aligned planes are generally boring. The best of them is Limbo, which is mostly a featureless plane but has some areas that are irregular mixes of earth, water, fire, and air. In other words, the best part of Limbo is a lot like the 4e Elemental Chaos, which is among my least favorite 4e planes. My favorite thing about Limbo, though, is that it is an area of “wild magic” where you must make a saving throw or roll on a table for a random hilarious effect. If you must adventure here, this will spice it up. Grade: C

The neutral-aligned planes are generally boring. The best of them is Limbo, which is mostly a featureless plane but has some areas that are irregular mixes of earth, water, fire, and air. In other words, the best part of Limbo is a lot like the 4e Elemental Chaos, which is among my least favorite 4e planes. My favorite thing about Limbo, though, is that it is an area of “wild magic” where you must make a saving throw or roll on a table for a random hilarious effect. If you must adventure here, this will spice it up. Grade: C

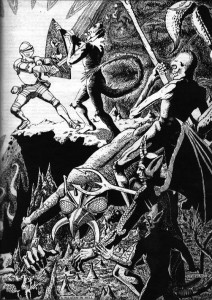

The evil-aligned planes are chock full of demons and devils. You have to have room for this in your cosmology, but the most interesting thing about them, to me, is that they inspired the epic picture “A Paladin In Hell”. Clearly, this paladin just went to hell so that he could kill an endless stream of devils until he was overwhelmed. That’s pretty badass, but that’s the only sort of adventure the evil planes suggest to me: a suicide mission, the object of which is to pile up demon corpses. That and trying to snipe Asmodeus for the XP. Grade: C

Sigil: The ultimate urban adventure location, Sigil connects to all the other planes, but why would you want to go to any of them? They’re all worse than Sigil. Sigil has interesting politics, people to fight, and badass goth NPCs like the Lady of Pain. With its distinct neighborhoods, its commerce, and its superiority to all other travel destinations, it’s a lot like a New Yorker’s idea of New York. Grade: A

Overall Grade of the Great Wheel Planes: D-

Obviously I don’t understand the fun that can be had with the Great Wheel. Someone tell me anecdotes about the great times they had doing planar adventures – besides Sigil, which I agree is awesome.