In Men & Magic, Gary Gygax says that D&D is “strictly fantasy. Those wargamers who lack imagination, those who don’t care for Burroughs’ Martian adventures where John Carter is groping through black pits, who feel no thrill upon reading Howard’s Conan saga, who do not enjoy the de Camp & Pratt fantasies or Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser pitting their swords against evil sorceries will not be likely to find DUNGEONS and DRAGONS to their taste.”

Re-reading Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars recently, I was struck with how explicitly it’s a Western. John Carter fights savages on dead sea bottoms, gropes through caverns looking for treasure, and fights weird monsters. And that’s all before he goes to Mars. The first episode of the novel is a shoot-em-up Arizona adventure which encapsulates all the rest of the book. Mars is Arizona writ large, with bigger and drier deserts, more savage natives, more accurate guns, faster horses, and more faithful dogs. In structure, the book is a lot like the Wizard of Oz movie: a reasonably plausible day, followed by a fantasy dream sequence version of the same events.

Re-reading Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars recently, I was struck with how explicitly it’s a Western. John Carter fights savages on dead sea bottoms, gropes through caverns looking for treasure, and fights weird monsters. And that’s all before he goes to Mars. The first episode of the novel is a shoot-em-up Arizona adventure which encapsulates all the rest of the book. Mars is Arizona writ large, with bigger and drier deserts, more savage natives, more accurate guns, faster horses, and more faithful dogs. In structure, the book is a lot like the Wizard of Oz movie: a reasonably plausible day, followed by a fantasy dream sequence version of the same events.

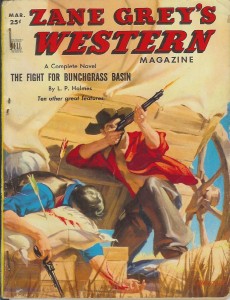

The second of Gygax’s sources, Howard’s Conan, is similar. Howard was a Texan who wrote Westerns along with his fantasy stories, cowboys-in-the-Middle East stories, and boxing stories. It’s frequently argued that Conan is a Western hero. His martial skills allow him to triumph over the lawless savages and over the decadent “civilized” folk of his wild land. That’s what cowboys do.

That’s two of Gygax’s Big Four. De Camp & Pratt and their characters are highly-educated scientists and historians, and Leiber and his heroes are urban goofballs. D&D is inspired by no one tradition. But if you scratch the surface, you’ll find that D&D is as much Boot Hill as it is Tolkein.