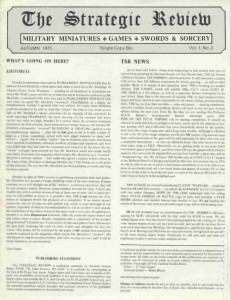

Strategic Review 3, published in 1975, has an extra long “creature feature” introducing 9 new D&D monsters. It tends heavily towards gimmick monsters designed to infuriate PCs, usually by setting traps that the PC can’t realistically avoid. Most of these monsters went on to become beloved fan icons, proving how weird D&D players really are.

Strategic Review 3, published in 1975, has an extra long “creature feature” introducing 9 new D&D monsters. It tends heavily towards gimmick monsters designed to infuriate PCs, usually by setting traps that the PC can’t realistically avoid. Most of these monsters went on to become beloved fan icons, proving how weird D&D players really are.

The original D&D monster book, the 1974 “Monsters and Treasure”, had its fair share of “gotcha” monsters: the Black Pudding, which Gygax called a “nuisance monster”, which divides when attacked with weapons; the ghoul, which could paralyze on touch; the various undead monsters which stole character levels. The dungeons of OD&D are dangerous, and sometimes people die. But the monsters published in the Strategic Review took it to a new level. Here are the 9 creatures introduced in SR#3, along with a Gotcha! rating of 1 to 5.

Yeti: The yeti is actually a pretty stand-up guy: sure, it paralyzes you with its gaze if it surprises you, and it has a 85% chance of surprising a party of its level, but apart from that, the yeti fights fair. It even takes extra damage from fire attacks. Somehow, though, it didn’t make it to the status of iconic D&D monster. I guess there’s no room in D&D for pushovers.

Gotcha level: 2/5

Shambling Mound: I believe Gygax said that the Shambling Mound was based on one of the Swamp Thing-like superheroes. It’s crazy tough.

First of all, it has 6-9 Hit Dice, and the Hit Dice are noted as being d10’s. I’m not sure why it has better, instead of more, Hit Dice, unless it’s so that the referee can justify using it to kill level 6-9 characters.

Secondly, it has resistances to everything. Compare it to the “nuisance monsters” of the 1974 Monsters and Treasure book, which have a handful of resistances: “The ochre jelly can be killed by fire or cold, but hits by weaponry or lightning bolt will merely make them into smaller Ochre Jellies.” “Black Puddings are not affected by cold. It is spread into smaller ones by chops or lightning bolts, but it is killed by fire.” “Green Slime can be killed by fire or cold, but it is not affected by lightning bolts or striking by weapons.” Etc.

For the Shambling Mound, though,

most hits upon it do but little damage (thus Armor Class 0). As it is wet and slimy, fire has no effect, lightning causes it to grow (add 1 hit die), and cold does either one-half or no damage due to its vegetable constitution. All weapons score only one-half damage. It can flatten itself, so that crushing has small effect upon the Shambler.

That’s pretty much every type of damage that it’s immune to, takes half damage from, or becomes stronger from. That, combined with its AC 0 and its d10 HP, make it pretty much a guaranteed session-long battle (if the PCs can last a session). Luckily,

Plant Control and Charm Plants are effective.

which is good news for all the 14th-level wizards who memorized Charm Plants for their 7th-level spell slot instead of Limited Wish, Delayed Blast Fireball, or Power Word Stun. It’s bad news for people who memorized “Plant Control” because as far as I can tell, that doesn’t seem to be a real OD&D spell. [Edit: OK, I found Plant Control. It’s a potion.]

Gotcha level: 4/5

Leprechaun: This annoying, mostly noncombat creature “will often (75%) snatch valuable objects from persons, turn invisible, and dash away. The object stolen will be valuable, and there is a 75% chance of such theft being successful.” Pretty irritating, but at least “Leprechauns have a great fondness for wine, and this weakness may be used to outwit them.”

Gotcha level: 3/5

Shrieker: The only function shriekers have are to give the GM a few extra wandering monster rolls. It’s “unfair” in that it’s unavoidable (they shriek when light gets within 30′, so how are you supposed to see them?) but it actually strikes me as the kind of unfair that adds energy to the game table, not subtracts it.

Gotcha level: 2/5

Ghost: Ghosts have various attacks that they can make on you, but you can’t make attacks back at them because they are non-corporeal. They sometimes do take on corporeal form, which is when you have a fighting chance. Or is it?

They otherwise attack by touch which causes aging of from 10 to 40 years, but in order to do this they must assume a semi-corporeal form, and when they do so they may be attacked by magic weapons (but not spells) as if they were Armor Class 0.

They have a unique aging attack (two hits from which will kill your human character’s adventuring career). No matter what level you are, good luck carving through all of the ghost’s 10 Hit Dice (with weapons, not spells) before he hits you twice. That’s beside the fact that, presumably, ghosts can return to spirit form whenever they want.

Gotcha level: 5/5

Naga: There are three types of naga, roughly mapping to Lawful, Neutral and Chaotic. They get magic-user and cleric spells, but they don’t have spellcasting ability in excess of their Hit Dice. About the roughest thing they can do is “permanently Charm the looker unless save vs. paralization is made”, but hey, at least you get a save.

Gotcha level: 1/5

Wind Walker: Spooky telepathic storms that, like ghosts, are ethereal, so “Wind Walkers can be fought only by such creatures as Djinn, Efreet, Invisible Stalkers, or Aerial Servants.” If you’re just a PC, you’re pretty much out of luck. There are a handful of spells that have some effect on them (interestingly, Control Weather kills them, and Slow acts like a fireball), but if your spells can’t deplete the Wind Walker’s 6 Hit Dice, you’re in trouble.

Everyone within 10′ of a Wind Walker automatically take 3-18 points of damage. That’s a lot, considering that in OD&D, you earn 1-6 HP per level. There’s clearly been a lot of damage inflation since OD&D Monsters and Treasure, in which a troll (6+3 HD) does one die of damage and giants (8-12 HD) do two dice. It will only take 3 or so turns for a single Wind Walker to wipe out even high-level Superheroes and Wizards. Here’s the rest of the bad news: “Wind Walkers will pursue for 10 turns minimum.”

Oh, there was a piece of bad news I forgot: “Number appearing: 1-3”

Gotcha level: 4/5

The Piercer:

With their stoney outer casing these monsters are indistinguishable from stalagtites found on cave roofs. They are attracted by noise and heat, and when a living creature passes beneath their position above they will drop upon it in order to kill and devour it.

The penultimate “gotcha” monster, piercers are undetectable until they drop onto an adventurer for a confusing “1-4 dice (6-24) damage.” 1-4 dice seems to describe a range between 1-6 and 4-24 damage; I’m not sure where 6-24 comes from.

Although I don’t understand the damage equation, it’s clearly a lot of damage. And piercers come in groups of 2-12.

The piercer’s initial assault is bad enough, but they presumably keep fighting until they are killed, doing an additional 6-24 damage on every hit. It’s the gotcha that keeps on gotcha-ing.

I think the right thing to avoid death by Piercer is to Fireball every square foot of cavern ceiling before you walk underneath. Enjoy your treasure type Nil!

Gotcha level: 5/5

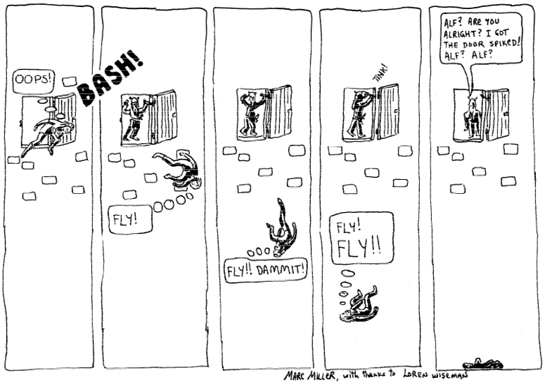

The Lurker Above: The ultimate “gotcha” monster, “its greyish belly is so textured as to appear to be stone, and the Lurker typically attaches itself to a ceiling where it is almost impossible to detect (90%) unless actually prodded.”

OK, so the defense is to prod every ceiling? No, because “when disturbed the Lurker drops from the ceiling, smothering all creatures beneath in the tough folds of its ‘wings.'” Clearly, the DM is going to drop this guy on your party whether or not you try to detect it.

Once the DM has sprung his trap, “this constriction causes 1-6 points of damage per turn, and the victims will smother in 2-5 turns in any event unless they kill the Lurker and thus break free. … Prey caught in its grip cannot fight unless the weapons used are both short and in hand at the time the creature falls upon them.”

Who always carries unsheathed short weapons? Not the fighter; he’s got a sword. Not the cleric either. The magic user might have his dagger out. But your hopes are really pinned on the party Thief. Can he kill the Lurker Above in 2-5 turns? Well, the Lurker Above has 10 Hit Dice. Given the generous assumption that the Thief can get in 3 hits before he smothers, can he do an average of 10 damage per hit?

Gotcha level: 5/5

Like most of my projects, this one has succumbed to “featuritis” – it’s a lot more ambitious now that it was when I started programming. Here are some of the features I didn’t know I needed until I added them:

Like most of my projects, this one has succumbed to “featuritis” – it’s a lot more ambitious now that it was when I started programming. Here are some of the features I didn’t know I needed until I added them: