At the foot of the little rise there was a map of the world, carte du monde, mappamondo, karte der welt, with the countries marked on it in brilliant colors. I knew that if I wanted to go anywhere, from Angola to Paphlagonia, all I had to do was put my foot on the spot.

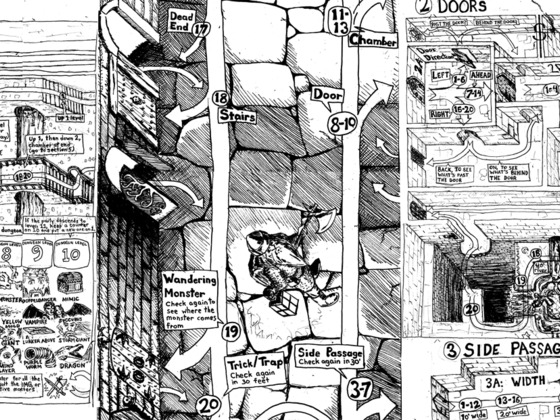

This quote from Sign of the Labrys got me thinking about how few magical maps there are in D&D. (Between proofing my Random Dungeon poster and working on my stretch-goal board game rules, I’m in a mappy place right now anyway.)

Maps are very important to the play of OD&D. Graph-paper maps are the primary archaeological product of an old-school D&D game, along with empty Mountain Dew bottles. Furthermore, in-game maps (treasure maps) are a big part of OD&D treasure. Nevertheless, there are virtually no magical maps. There might be one or two in splatbooks, but I don’t think any core Dungeon Master’s Guide has ever featured a magical map. (The 1e DMG, on the other hand, has four different magical periapts.)

Contrast this with computer games. A magical map is one of the ubiquitous items in computer RPGS: so common that it’s part of the user interface. Nearly every game comes with an auto-map. I’m splitting hairs here a little: I know that, within the fiction of the game, most auto-maps represent the cartographic efforts of the main character. Still, if you’ve played old games like The Bard’s Tale where you did your own mapping on graph paper, auto-maps feel pretty darn magical.

Here are some magical maps for D&D. They join a proud tradition of D&D’s brilliant “you now have permission to ignore the rules” magic items. They don’t really give the players new powers: they enable a free-and-easy play style that some prefer. Don’t like encumbrance? Have a Bag of Holding! Don’t like tracking light sources? Everburning torch!

Along with each magic map are notes about what play style it might support.

AUTOMAP PAPER

Automap paper looks like ordinary paper until a drop of ink is applied to it. The ink will crawl of its own accord, drawing a small overhead map view of the PC’s current location. If the PCs are inside a structure, the picture will be scaled so that the entire floor of the building could be drawn on one sheet of paper. If the PCs are outside, it will be scaled so that the entire island or continent can be drawn. Detail level will be appropriate to the scale.

Once the map has been started, it will automatically update itself whenever it’s in a new location. It can’t map while it’s inside a container: it needs to be held in a hand or otherwise out in the open.

Players can draw annotations on the map if they like.

Using automap paper in a game: Start a campaign for a new-school D&D group (3e or 4e) and make them map the dungeons. If they haven’t done so before, every group should map a few dungeons. However, not every campaign is dungeon-crawl focused, and so, once the players have run the gauntlet a few times, let them find a sheaf of, say, 50 sheets of automap paper. From then on, let the players peek at your DM map if they ever get lost. This strategy goes with the general progression of level-based games: start with lots of restrictions, and slowly lift them.

This item also works well in games where the DM draws out the important locations on a battlemat.

Because every magical item should have a leveled version, here are some improved versions of Automap Paper:

Architect’s Map: This superior version of automap paper is blue, and requires white chalk to activate it instead of ink. It draws a whole dungeon level at once, without requiring you to visit each part, and automatically shows hidden and concealed doors, as well as any trap that was built as part of a building’s original construction.

Using the Architect’s Map in a game: Give the PCs a copy of the DM map. It’s up to them to track their journey and to notice your notations for traps and secret doors. While automap paper can be given freely to PCs, an Architect’s Map might be a limited resource: players might find 1d4 sheets at a time. An architect’s map is especially good when you don’t mind letting the players making informed decisions about where to go.

Living Map: This is the Harry Potter version of the automap. It uses moving dots of ink to represent all living things on the map. A cluster of 10 hobgoblins might look like one large dot, and be indistinguishable from five hobgoblins, or from a dragon.

Using the Living Map in a game: Like the Architect’s Map, this should be an expendable resource. It’s handy in an ordinary dungeon: it’s nice to be able to check the map to see if there’s an ambush behind the door. It’s even more useful for heist, stealth, or chase adventures. It’s a nice magic item for groups that like to outthink obstacles instead of killing everyone in their way: in other words, give it to your Shadowrun group when they’re playing D&D for a change. Keep in mind that a single piece of map paper only graphs one floor. If a creature goes upstairs, it’s off the map.

Travel Map: If a character touches a point on this automap, he or she will instantly travel to that location. Keep in mind that the automap only charts visited places, so a character cannot use it to travel somewhere new. Also, a travel map can only teleport a single player: since the map travels with the player, it can’t be used for party travel.

This map’s special properties are only available if its owner is in the mapped area: in other words, a player can’t use a travel map of a dungeon to teleport into the dungeon. He or she may only teleport from one point in the dungeon to another.

This map is especially useful as an outdoor map: travel between cities is usually more time-consuming and difficult than travel between different rooms in a dungeon.

Using a travel map in a game: A single piece of travel map paper, used as a continental map, can expedite the kind of fast-travel used in most computer RPGs. The first time you go somewhere, you have to go there the hard way. Once you’ve been there, you can hand-wave any future travel to or from that location. A single travel map allows a single character to take intra-continental jaunts, allowing for lots of communication and resupply options; more useful fast travel requires enough maps for the whole party. A pack of travel-map paper is a pretty good find for a high-level party which is outgrowing wilderness adventures.

A fun trick: Don’t let the players know that their map is of the “travel map” variety. Watch the players during the game. When someone touches a spot on the map to make a point, tell everyone that that player’s character has disappeared.

It’s not necessary to posit a specific literary model for the Brooch of Shielding: it’s not too hard to come up with an item that protects against missile attacks. Still, here’s a plausible literary source: a passage from Gardner F. Fox’s 1964 Warrior of Llarn, written by an author Gary Gygax admired (and who is part of the Appendix N pantheon) at a time when Gygax was reading practically all the sci-fi and fantasy that came out.

It’s not necessary to posit a specific literary model for the Brooch of Shielding: it’s not too hard to come up with an item that protects against missile attacks. Still, here’s a plausible literary source: a passage from Gardner F. Fox’s 1964 Warrior of Llarn, written by an author Gary Gygax admired (and who is part of the Appendix N pantheon) at a time when Gygax was reading practically all the sci-fi and fantasy that came out.