I’m pretty close to finishing up my monster design guidelines based on reverse-engineering the Monster Manual. Before that, though, I want to comment on an interesting episode of DM’s Deep Dive in which Mike Shea (Sly Flourish) interviewed D&D lead rules designer Jeremy Crawford about monster design.

Mike asked Jeremy about the table in the DMG for homebrewing monsters. It’s public record that I have my doubts about that table. Jeremy provided this interesting fact: apparently, the canonical formula for determining monster CR is encoded in an internally-used Excel spreadsheet. (We’ve seen this spreadsheet in action in the Mike Mearls Happy Fun Hour.) The table in the DMG was made after the spreadsheet, and was an attempt to reverse-engineer and simplify the spreadsheet’s formulas for DM’s home use: it’s not used as part of the process for creating for-publication monsters.

My research indicates that while D&D monster stats are internally consistent and carefully designed, their power levels don’t line up well with the DMG chart. This leads me to believe that the spreadsheet does what it intends to do, while the DMG chart does not.

I invite you to ponder this further mystery from the Deep Dive podcast:

In the podcast, Jeremy Crawford talked about how the D&D team approaches what he calls “action denial” attacks: paralysis, charm, etc. This is something I’ve wondered about. My initial research suggested that these attacks didn’t have much of an effect on CR, which I though was strange: taking out a combatant for a few turns seems like it should be a powerful ability.

Jeremy used paralysis as an example to illustrate the team’s approach. First, find the lowest-level spell which inflicts a condition. For paralysis, that’s Hold Person. Next, you translate that into damage by finding the damage output of the simplest pure-damage spell of that level. Hold Person is level 2, and its comparable damage spell is Scorching Ray, which does 6d6 (21) damage. Thus, the ability to paralyze is worth 21 “virtual” damage for Challenge Rating calculation purposes.

I see the logic in that, but it doesn’t scale the way I’d expect it to. If you’re fighting four opponents, I’d expect the ability to keep one of them paralyzed to be worth, say, 33% extra virtual hit points (the hit points you won’t be losing to the paralyzed opponent) – or some similar scaling benefit. If the ability is expressed as flat damage, 21 hit points damage is dominant at low levels and negligible at high levels.

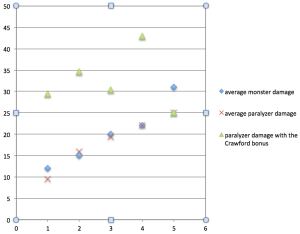

And indeed, when checked against monster data, it doesn’t seem as if monsters are balanced exactly as Jeremy describes. Check out the chart below. This includes all ten CR-5 or lower monsters with a paralysis attack: the carrion crawler, chuul, ghoul, ghast, grell, pentadrone, mummy, revenant, thri-kreen, and yeti. (Above CR 5, the 21 virtual hit points of paralysis would rarely be relevant to CR because monsters generally have a more damaging attack options.)

In this chart, the blue diamonds represent the average damage output of a monster of each CR from 1 to 5. The red X’s represent the base damage output of paralysis-inducing monsters – without the 21-point “Crawford bonus.” As you can see, the paralyzer damage is very close to average monster damage.

The green triangles represent the average damage of paralyzers, once you take the 21 points of “virtual damage” into account. As you can see, adding this would skew monster damage way too high – doubling their effective damage in most cases! If this damage were really being taken into account the way Jeremy describes, all these low-level monsters would have to have very low-damage attacks – a ghoul with a claw doing 1 damage, for instance – to make room for all that virtual damage.

This is one of those unaccountable situations, like many others that we’ve discovered while investigating how monsters are built, where the WOTC instructions for building a monster don’t match the monsters we see in the manual.

My best guess for why this is: playtesting. It’s possible that monster stats started off skewed and exception-ridden. How could they not? It’s an incredibly complicated system. But then through the public D&D Next playtest, the NDA playtest, the internal playtest, and the good intuitions of the designers themselves, the proud nails were hammered down. Monsters were adjusted until they felt right. The tyranny of the spreadsheet was overthrown by humans, or at least reformed into a constitutional monarchy. And so, while the designers of D&D may be still using an occasionally flawed formula to initially prototype their monsters, they’re compensating for the Excel spreadsheet’s failings in later steps of design.

It’s interesting to compare the designers’ intent (as evidenced by what we know of their monster-design process) to the final product (the monsters in the rule books.)

The intent is to account for everything in a monster’s CR. Hundreds of monster traits are weighed to the fraction of a CR. Changing one stat has a ripple effect on other stats. As Jeremy said in the podcast, they’re still using the same Excel spreadsheet that they’ve been using for five years. I’m a programmer and I know what that means. Complication is added to complication, all adding up to the illusion of precision. No one really knows how it works anymore: look how hard it is to reverse engineer (see that DMG table I’ve been complaining about). From this end of the process, monster design has a baroque, stately, creaking majesty.

The final product, when analyzed, is simple, flexible, and streamlined. Challenge Rating gives a broad bell curve of possible hit points and damage outputs. Tweaking one number doesn’t affect another. A monster’s traits and special abilities have no significant, measurable effect on its Challenge Rating: every monster gets its schtick and they all sort of balance out. From this end, monster design appears to have a flexible, easygoing, organic solidity.

This is a common pattern in tabletop game design. Things start complicated. The more they’re used at the table, the simpler they become. I think Jeremy and the rest of the D&D team are geniuses, but their real genius lies in knowing and respecting the value of playtesting.

I don’t really see any evidence of genius on the part of the design team. Quite the contrary, in fact.

There are two reasonable ways to approach assessing monster toughness – straight calculation, and monte carlo methods. Of the two, monte carlo methods are the obvious correct choice for all but trivial cases. Delta has been using this approach to good effect for some time (years?). It boggles my mind that professional game designers are not.

By simulating the outcome of fights under various conditions, you don’t need to guess at how strong the paralysis attack is – the simulation will tell you.

Crawford et al have opted for calculated strength, but rather than sitting down and doing the hard work of actually doing the requisite calculations, they’re relying on heuristics like the “find the lowest-level spell with a similar effect etc.” method that, as you quite rightly point out, simply *do not work*. Not that there’s any reason to expect that method to work. It’s madness.

They are using methods that are obviously not going to produce a reasonable result, then, as you again rightly point out, use playtesting to correct their bogus results. And rather than the playtesting being a forehead-slapping moment for them, and a chance to throw out their flawed methods, they just keep on rolling, using an *Excel spreadsheet* based on junk data for *years*.

I am thoroughly unimpressed by their design acumen. As usual in RPGs, the hobbyist community is running circles around the so-called professional designers.

I should also say that I’m finding your analysis of CR as it is very interesting. You’re doing the good and thankless work of turning over stones and seeing what strange things lie beneath.

Oh dear lord, I typoed blogspot as blogpsot and the link is going to the weirdest website lol… oh dear.

Only noticed because I wasn’t able to successfully follow the comments.

This is my actual blog/site:

http://spellsandsteel.blogspot.com

Charles, do you have a link to Delta’s Monte Carlo sims? That is, as you say, obviously the best way of assessing monster toughness, and I’m interested to see his results.

BTW I love your blog’s take on Alignments that Aren’t Stupid.

-Max