Last week, I played D&D with Mike Mornard, a member of the original Greyhawk and Blackmoor campaigns. This is the last piece of my writeup of Mike’s wisdom.

monsters

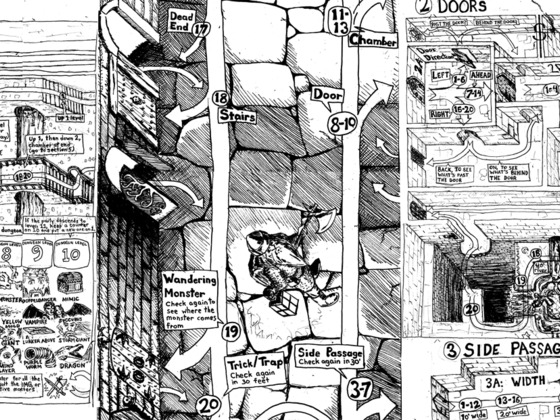

Mike cried fie on the modern-era concept of PC-leveled encounters. (I don’t remember if he actually said “fie,” but he is the sort of person who would have said “fie” if he thought of it, so I’ll let it stand.) In Greyhawk, you might encounter trolls on level 1 of the dungeon. There would be warnings: skulls and gnawed bones, and the party dwarf might notice a trollish stench. I asked, “Would there also be skulls and gnawed bones in front of the kobold lair?” meaning to ask if the danger warning signs were applied to every monster, weak and strong alike. It turned out to be a bad question: despite their lousy hit points, the badassification of kobolds started on day 1 in D&D. Gygax’s kobolds were deadly. Mike said that they collected the magic items of the characters they killed, which meant that besides their fearsome tactics, they also had a scary magical arsenal.

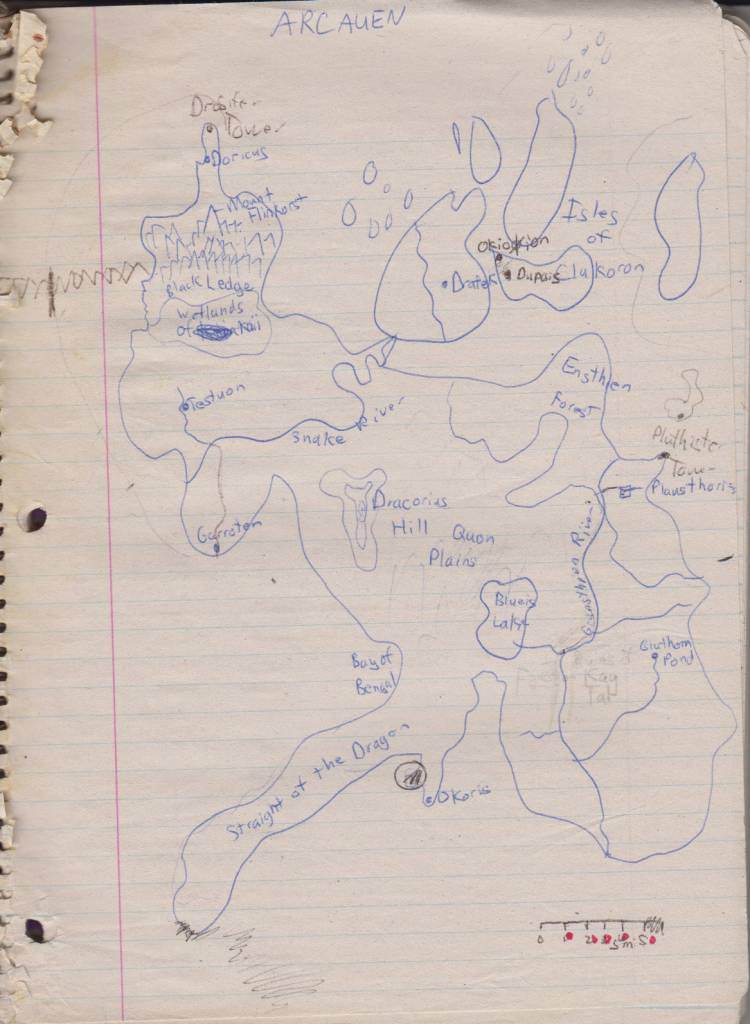

When Mike started DMing, lo and behold, the first monsters we fought were… kobolds! The first signs we saw of them were stones whizzing from the darkness to hit our PCs. We chased the stone-throwers into passages, around corners, and past intersections, never sure if we were on the right track. We managed to corner two kobolds, killing one and Charming the other. We tried to interrogate the kobolds, but none of us spoke kobold (we should have thought of that before we wasted our wizard’s only spell, I guess.) We gave the Charmed kobold my map and tried to pantomime for him to complete it, which I thought was pretty clever, but he filled the paper with pornographic kobold scrawls. Couldn’t have been much less helpful than my map.

We spent the entire session chasing down four more kobolds. They dropped two of us to 0 HP, and it was touch and go whether the rest of us would make it out of the dungeon. Here, again, light was an important factor: since we had torches, we were great targets for stone-throwing creatures in the darkness. Eventually, we started setting ambushes in the dark; surrounding our position with torches so that the kobolds would have to show themselves to attack; and, most importantly, planning fast. Every time we spent too much time in deliberation, another sling stone would come flying out of the darkness.

Mike later mentioned that he’d given kobolds an affinity for stones because, in Chainmail, kobolds were sort of the monster equivalent of halflings, and halflings also had bonuses with stones. Also, kobolds are traditionally mining spirits: the element cobalt is derived from the name kobold.

After the game, Mike told us that he’d run this adventure before, and we’d done better than a lot of groups, because we were fairly focused and we played with a minimum of “cross-chat”. We did a little out-of-character and in-character joking around, but less than most groups I’ve been in: both because delays tended to get us attacked, and because we were in a noisy art gallery where we had to strain to hear the DM.

That’s not to say that there was no joking among the players, and the DM wasn’t entirely serious either. In choosing the kobold mine, we passed up several adventure hooks, including one involving getting back a sacred bra or something – I wasn’t interested in that because it didn’t seem serious enough. I guess I’ve come to expect relative seriousness from the DM and silliness from the players, while Mornard-style OD&D seems to involve seriousness from the players and silliness from the DM. Mornard has said elsewhere that D&D is a “piss-take” – a send-up of the fantasy and wargames of the 60s and 70s. If that’s the case, it’s especially funny that D&D has outlived the things it was parodying. It’s as if the audiophiles of the future had to piece together the music of the 80’s and 90’s entirely from Weird Al albums.

Speaking of humor: Mike recommended the Book of Weird, a “humorous dictionary of fantasy” that he said was great reading for a DM.

treasure

When we finally found a part of the mine that was studded with gems, we grabbed the gems and ran – we didn’t care what else was in the dungeon. We ended up with 27 gems: Mike gave our fighter bonus XP for being cautious enough to pry the first one out with a ten-foot pole.

When we got back from town, Mike rolled up the values of all the gems, announcing the value of each to the party record-keeper (me, again my default). If I were the DM, I probably would have announced an average value of the gems or something: I wouldn’t have thought the players wanted to sit through a list of 27 numbers. But it’s funny: people’s attention spans get longer when it comes to profits.

The random rolling paid off for us when, among the other gems, we found a 10,000 GP-value gem. That pushed us all up to level 2. Mike commented that that’s why he likes random charts: they help tell a story that neither the DM nor the players can anticipate.

character classes

As we were making our characters, and the cleric was exclaiming over the lack of level spells, Mike told us a little bit about the evolution of the classes. A low-level OD&D cleric, he reminded us, was a capable front-line fighter – kind of an undead specialist warrior – especially in the early days of D&D, when every weapon did 1d6 damage.

One of the effects of variable weapon damage, he said, was to make weapon choice more plausible and meaningful. Before variable weapon damage, everyone was using the cheapest weapon possible – iron spikes! After variable weapon damage, fighters started using swords, which did 1d8 damage, or 1d12 against large monsters. Fighters with swords was a better mirror of history and heroic fantasy than fighters with daggers or iron spikes.

combat rules

Mike played with pretty straight OD&D rules with the Greyhawk supplement. He says that Gary’s group played with variable weapon damage, including different damage for medium and large opponents, but not the AD&D weapon speed rules.

In our game, when Mike called for initiative, each player rolled a d6 at the beginning of each round. Mike would call out: “Any sixes? Fives?” etc, so a high roll was good. I don’t know if that’s what they did in Gary’s game, but it worked for us in 2012.

Mike told us that, while he was in Dave Arneson’s game, they mostly played straight OD&D. They didn’t use the hit-location rules from the Blackmoor supplement: Mike doubts that anyone ever played with those. But who knows: “people were bringing in new rules all the time,” he reminded me, “and not everything stuck.” Mike also didn’t remember anyone using the assassin. Too bad: I’m pretty curious about how that class actually worked in play.

One last comment about Gary Gygax: When Mike joinde Gary’s game, Mike was 17 years old. “Gary was the first person who ever treated me like an adult,” he said. Not a bad legacy, even apart from the cool game.