With my DM Mike Mornard moving from New York (he finished school and got a job! congratulations!) my OD&D game will end. I’ve enjoyed the high-mortality dungeoncrawl during the six months or so I had Mike as my DM. It’s been a great complement to my 4e game.

We got together for one last OD&D game: we all met up in the afternoon and played till 1 AM, ordering pizza at the game table. It felt like an archetypical game session to me, and Mike compared it to the games he used to play when he DMed for Phil Barker. Those games, which also typically wrapped up around 1 AM, were played at a time when the iron of D&D was still white hot off the forge. Sparks kindled. As Mike told us, “Whenever we introduced someone to D&D, they’d come back in a week or two with a dungeon they wanted to run.” Phil Barker, of course, came back to Mike’s group, after considerably more than two weeks, with Empire of the Petal Throne.

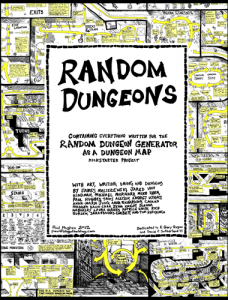

our dungeon map

One of the reasons we played so late (on a work night!) was that we wanted to finish our maps of level 1 of the dungeon. Tavis Allison and I were both mapping (his maps look nicer than mine do), and we both wanted to fill in the last dead-end corridors to complete the unbroken line bounding the borders of the dungeon. Like summoning circles, dungeon maps with gaps in the borders can be very dangerous.

I’d like to give you a scan of the map, but I can’t find it at the moment. Anyway, it’s not necessary. If you saw it, you’d recognize it, in its general outlines, as the sample dungeon in the 1e Dungeon Master’s Guide, as it would appear if it were mapped by a somewhat inexpert cartographer.

In session 1, a player realized that we were in the 1e dungeon. During the campaign, I made sure not to look at that dungeon: I wanted no refreshers about dungeon layout or contents.

As it turns out, it wouldn’t have mattered much. There are only a handful of encounters in the DMG, and Mike changed several of them anyway. In the large central chamber, instead of a puzzle leading to a secret door, Mike put one of his NPC characters, Necross the Mad. Every interaction with Necross was a negotiation, where we traded something (usually not treasure) for passage through the room. By the end of the campaign, we were quite chummy with Necross, despite the fact that he claimed to have plans to destroy the universe.

Actually, come to think of it, we didn’t map ALL of level one. Somewhere in the dungeon, we Charmed an evil cleric. He complained endlessly about how his superiors didn’t appreciate him (ah, the banality of evil). Between complaints, he warned us of a troll nest to the north. Later, when our dwarven fighter announced that he smelled a terrible trollish stench, we turned around. Sure, we wanted to complete our map, but low-level OD&D characters don’t become high-level by being stupid.

arise sir roger

My thief character, Roger de Coverley, was named, somewhat randomly, after an 18th century dance, the Sir Roger de Coverley, that appears in a lot of old novels. Having given my character this name, I decided that his destiny was to be knighted and then to invent the dance. Most of my character’s decisions were made with my knightly ambitions in mind. Figuring that every knight needed property and followers, I tried to gather money, hire troops, and have other PCs swear fealty to me.

The gathering-money goal turned out to directly conflict with the gain-followers goal. In my attempt to keep everyone alive, I bought plate mail for everyone I hired. Furthermore, when NPCs died (and they died a lot, even with the plate mail), we felt duty-bound to get them Resurrected. It wasn’t good business to spend thousands of GP to resurrect a guy who earned a gold piece a day, but it kept the NPCs happy. In Mike’s game, it’s hard to keep NPC hirelings happy. (As he says, “Loyalty is a luxury the poor cannot afford.”) Our health care plan seemed to do the trick. It left me poor, though. By our last few sessions, we were starting each adventure trying to raise money to resurrect a dead henchman. In the dungeon, we’d raise the money we needed – but lose another henchman along the way. It was like a resurrection Ponzi scheme.

Besides Necross the Mad, the other main NPC of Mike’s campaign was Lord Gronan. The dungeon was below his throne room: apparently he used the dungeon as a sort of Darwinian training ground for high-level heroes. When, at level 1, I offered to join his service as a knight, he told me, “Perhaps one day, if you prove yourself.”

Before our last trek into the dungeon, a level-five Roger de Coverley was summoned to Lord Gronan’s audience chamber. “I’ve watched you over the last months,” he said. “You have displayed the knightly virtues: you’ve been honest and you have guarded and served your followers. Too few remember that knighthood is about service.” Lord Gronan asked for Roger’s oath of fealty and dubbed him knight.

No sooner had Roger reached the summit of his ambitions than a new hireling joined the party: a female thief, a gold-digger who had clear designs on becoming Lady de Coverley. With Roger’s 7 Wisdom, I don’t expect he’ll be able to escape her toils.

off the edge of the map

The last time we passed through the dungeon, I told that unpredictable dungeon denizen, Necross the Mad, “It has been an honor and a pleasure exploring your dungeon.” I could have said that to Lord Gronan as well, since he sent us into the dungeon in the first place. And I could have told it to DM Mike Mornard as well. It’s true in all three cases.

Our characters have survived the dungeon. We’ve finished the map (except for the troll den). Mike is off to re-explore the Midwest; Ben (the dwarf fighter) got a job in Virginia; Tavis (the pyromaniac fighter) will return with new OD&D tricks to his Red Box game; and, in our weekly new-school game, Andrew (the wizard) and I will explore the wilds of 5e. Time to start a new sheet of graph paper.