I’ve heard a lot of references to the 1981 module “In Search of the Unknown:” it came with the first edition of Basic D&D, and a lot of people have fond memories of it. I’ve never read it. When I got a heavy box of D&D books in the mail, it was the first module I grabbed.

I’ve heard a lot of references to the 1981 module “In Search of the Unknown:” it came with the first edition of Basic D&D, and a lot of people have fond memories of it. I’ve never read it. When I got a heavy box of D&D books in the mail, it was the first module I grabbed.

I’ve been on a search of my own lately, exploring the D&D I missed before I entered the hobby. As a kid, I played in bizarre junior high versions of Red Box Basic and AD&D, and as an adult I’ve mostly played third and fourth edition. It’s been fun playing OD&D: I’m slowly getting a handle on a different style of D&D than one I’ve ever played.

I was delighted to find Mike Carr’s lengthy “how to play D&D” essay at the beginning of the module. It’s pretty similar to advice in the OD&D and Dungeon Master’s Guide books, but since I’ve never read it before, it’s fresh. I have two other fresh experiences with which to compare the advice: my OD&D games with Mike Mornard and my extremely close study of Gary Gygax’s Random Dungeon Generation tables from the Dungeon Master’s Guide. There are a lot of parallels to draw here.

mapping

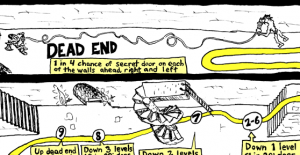

Here’s what Mike Carr says about the dungeon in In Search of the Unknown:

The dungeon is designed to be instructive for new players. Most of it should be relatively easy to map, although there are difficult sections – especially on the lower level where irregular rock caverns and passageways will provide a real challenge.

I didn’t realize until Mike Mornard spelled it out for us that mapping was intended to be one of the big challenges of D&D. The labyrinth is as dangerous as the minotaur. In Search of the Unknown is explicitly teaching mapping skills. The assumption is that more advanced modules will be bigger mapping challenges.

It is quite possible that adventurers (especially if wounded or reduced in number) may want to pull out of the stronghold and prepare for a return visit when refreshed or reinforced. If this is done, they must work their way to an exit.

When we play in Mike Mornard’s D&D game, he makes us use our maps. We can’t say “We leave the dungeon.” Every time, we have to specify our twists and turns back to the entrance. This still feels foreign to me. I think I’ve quoted Baf of The Stack before: a game is about what you spend your time doing. OD&D is a game about mapping. Exploration takes more game time than combat. Coming from 3e and 4e, I feel like I’ve been playing a different game.

I love the 1e Player’s Handbook illustration of the troll re-winding the twine trailed by the fighter. (I referenced it in my poster.) Mornard related this story: Once in Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor game, some guys decided to leave string behind them instead of mapping. Eventually, the rope jerked out of their hands and started unrolling, and then they heard a slurping, like someone eating spaghetti. Mapping is a necessary skill: don’t try cheat your way out of it.

I love the 1e Player’s Handbook illustration of the troll re-winding the twine trailed by the fighter. (I referenced it in my poster.) Mornard related this story: Once in Dave Arneson’s Blackmoor game, some guys decided to leave string behind them instead of mapping. Eventually, the rope jerked out of their hands and started unrolling, and then they heard a slurping, like someone eating spaghetti. Mapping is a necessary skill: don’t try cheat your way out of it.

caution

One player in the group should be designated as the leader, or “caller” for the party… once the caller (or any player) speaks and indicates an action is being taken, it is begun – even if the player quickly changes his or her mind (especially if the player realizes he or she has made a mistake or error in judgment).

Before playing in Mike Mornard’s game, my eye would have skipped over this classic bit of old-school advice as irrelevant to me. Now I’ve seen it in action:

DM: There are passages north and west.

US: We go south.

DM: Bump… bump… you bump into the wall.

More ridiculously, I recently had my thief start down the magic staircase into the chamber of Necross the Mad, even though I knew that the stairway hadn’t been summoned yet. A merciful DM would have reminded me of that fact – what adventurer would step off a ledge? – but Mike Mornard took me at my word, and I fell. Mike only gave me one point of damage, where perhaps Gary Gygax or Dave Arneson would have assigned more.

Mike says that his game is pretty close to the Gary and Dave game in rules and in content, but where their influences ran more to swords and sorcery, Mike brings more Warner Brothers to the table. There is a lot of laughing in Mike’s game, where Gary and Dave’s were grimmer. But in all three games – and in Mike Carr’s game as well – you need to listen to the DM, and visualize what you hear – and think. As Mike Carr’s introduction says elsewhere, “Careless adventurers will pay the penalty for a lack of caution – only one of the many lessons to be learned within the dungeon!”

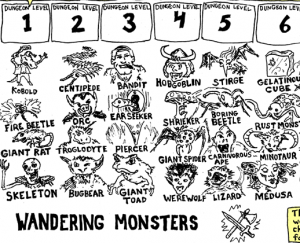

time

Every third turn of adventuring, the DM should take a die roll for the possible appearance of wandering monsters at the indicated chances (which are normally 1 in 6)… Some occurrences (such as noise and commotion caused by adventurers) may necessitate additional checks… Wasted time is also a factor which should be noted, as players may waste time arguing or needlessly discussing unimportant matters or by simply blundering around aimlessly. … You set the tempo of the game and are responsible for keeping it moving. If players are unusually slow… allow additional chances for wandering monsters to appear.

This passage will feel very familiar to the players in Mike Mornard’s game. We’ve all grown to fear the d6, which comes rolling out at us whenever we’re “needlessly discussing unimportant matters or simply blundering around aimlessly” – which is often. Wandering monsters disappeared from 4e (and from many 3e games) because they slowed down the game pointlessly. What Mike Carr is suggesting here, and what we’ve learned from Mike Mornard, is that wandering monster checks are actually a way to preserve pacing. Once you’re in the dungeon, you can’t afford to get bogged down in bickering over minutiae. How I wish that work meetings came with wandering monster checks.

This passage will feel very familiar to the players in Mike Mornard’s game. We’ve all grown to fear the d6, which comes rolling out at us whenever we’re “needlessly discussing unimportant matters or simply blundering around aimlessly” – which is often. Wandering monsters disappeared from 4e (and from many 3e games) because they slowed down the game pointlessly. What Mike Carr is suggesting here, and what we’ve learned from Mike Mornard, is that wandering monster checks are actually a way to preserve pacing. Once you’re in the dungeon, you can’t afford to get bogged down in bickering over minutiae. How I wish that work meetings came with wandering monster checks.

mysterious containers

The dungeon includes a good assortment of typical features which players can learn to expect, including… mysterious containers with a variety of contents for examination.

The typical D&D treasure announcement isn’t “You find 1000 GP in a chest:” it’s “You find an old wooden chest. What do you do?” Containers are important. The Appendix A random generator has three separate tables for rolling up characteristics of treasure containers. Here are a couple of the ones I’ve encountered in OD&D:

Contact poison on trap: One of the cardinal OD&D rules is “check the chest for traps.” As the party thief, I make sure to incant this formula. I think that the Greyhawk supplement has rules for finding traps, and I imagine that my odds of success are quite low, but in the last game, Mike told me, without requiring a roll, that the lock was covered with a brownish paste. Good enough warning for me to wear gloves. This transforms a 50/50 chance at arbitrary death into a game element that rewards a methodical, cautious play-style: quite in keeping with the mysterious OD&D “player skill.”

Contact poison on trap: One of the cardinal OD&D rules is “check the chest for traps.” As the party thief, I make sure to incant this formula. I think that the Greyhawk supplement has rules for finding traps, and I imagine that my odds of success are quite low, but in the last game, Mike told me, without requiring a roll, that the lock was covered with a brownish paste. Good enough warning for me to wear gloves. This transforms a 50/50 chance at arbitrary death into a game element that rewards a methodical, cautious play-style: quite in keeping with the mysterious OD&D “player skill.”

We considered taking the chest with us so we could brush it against opponents, but Mike’s beatific expression – that of a DM who’s thought of flaws in PCs’ plans – warned us to leave it where it was.

Invisible chests: Invisible chests are are oddly common in dungeons made with the Appendix A random generator – and hard to illustrate. They always seemed to me oddly pointless. Why include a treasure you can’t possibly find?

In our case, we passed the invisible chest on the way into a room, but tripped over it on the way out. I can imagine it working like OD&D’s 3 in 6 chance to fall in a pit: there are rewards, as well as dangers, you might never know you passed.

Our invisible chest contained 1000 or so gold, but we were all struck by the advantages of owning our own invisible chest. My character in particular, who frequently leaves his bandit hirelings unsupervised at home, has every need of a way to hide his treasure.

There’s probably a lot more of interest in In Search of the Unknown, but I’ll leave the rest unread – just in case I can get someone to run it for me. After all (says Mike Carr,) “this element of the unknown and the resultant exploration in search of the unknown treasures (with hostile monsters and unexpected dangers to outwit and overcome) is precisely what a DUNGEONS & DRAGONS adventure is all about.”

Tags: oldschool

My first ever game of Basic (this was in 2010, not the 70s–I also came to Basic through 3/4e) was with an already experienced group visiting B1. It was an utter bloodbath. The very first action I ever took in the game beyond introducing myself/etc was to lose initiative and be instantly struck down by an ochre jelly. Only an hour or two later, my second character was level drained down to 0 by a wight, and I was by no means the only player that lost two characters that night. Normally we manage to keep the body-count relatively low, but for some reason Quasqueton has developed a reputation with us as a place with tons of character death and relatively little treasure.

Go ahead and read the rest of it. Feel free. As one who was there when this first came out (in a yucky yellow cover, as I recall) reading the module doesn’t give you that much advantage – if any – in playing it. I ran it as GM a couple of times, then played in it. And it kept right on surprising me.

*jeep! & God Bless!

–Grandpa Chet

I actually ran this module with a 4e group – still learning to GM. At least I didn’t totally screw it up…

I tend to disagree with oldschool players on some of these issues. It’s one thing to let players reap the benefits of bad decisions. That’s good and necessary. But sometimes it seems as though oldschool GMs believe that they’re some kind of seeing eye dog for a group of deaf blind and dumb adventurers. If the players don’t grasp basic information about the environment (such as the presence of stairs, or lack thereof) then their character doesn’t notice them either.

I think some leeway is warranted. There’s a difference between being in an environment, and having an environment described for you.

Other than that, this article has given me a lot of great ideas to think about. Thanks for sharing!

Though I would describe my style as thoroughly old school, I’m with LS on this. As a referee there’s no way I would have a character walk off a cliff without double checking that we both had a similar conception of what was going on. I don’t think this gives away the special bits, because I am constantly asking my players for clarification and details, even for non-dangerous elements.

I wouldn’t do this in my 4e game, and while I might experiment with it in OD&D, I have a hard time actually picturing myself sticking to it. I’d describe my usual DM style as “generous.” I think I’d only play this way with a group who were all excited about playing an “authentic-style” OD&D game.

He had opened the secret door, and he had seen that the stairs were not there.

He then said he would step out into the room.

Remember: 50% Conan the Barbarian, 50% Daffy Duck.

In 4e I’d say to make a high DC Reflex check or he’d fall for the usual amount of d10s…

“High DC?” “Reflex check?” I know nothing of these things, but your words confuse and frighten me.

I’d like to comment on this bit:

“Wandering monsters disappeared from 4e (and from many 3e games) because they slowed down the game pointlessly. What Mike Carr is suggesting here, and what we’ve learned from Mike Mornard, is that wandering monster checks are actually a way to preserve pacing.”

I started playing in the ’70s, first with Holmes Edition, then a quick jump to AD&D 1e. Mapping and callers were pretty integral to the game then, at least in the groups I played in and DMed. Wandering monsters, though, were one of my favorite things when I DMed. I used them a lot. I can understand why you would say they “slowed down the game pointlessly,” as you come from the direction of 3e/4e first, but I never saw it that way, even in 3e and 4e.

Wandering monsters were integral to the game, too, though not always as a way to keep pacing brisk. That assumes that there is some kind of timetable or goal in the adventure or dungeon, something that needs to be accomplished by a certain point. In old school dungeons, at least the way I played and ran them, the goal, such as it was, was simply to explore.

In that respect, the wandering monster was just as much a part of the experience as a permanent (for lack of a better term) monster. For that matter, while my players knew some of the monsters were wandering, they didn’t always know when they were confronting a wandering or permanent monster, because I didn’t always show them the roll, or indicate what I was rolling for.

Plus, “wandering” does not equal “random,” so the critters they encountered, wandering or permanent, made sense in the context of the dungeon…at least to me, the DM. That pair of bugbears that showed up from around the corner may not baffle the players or the characters, because there were a lot of goblin-types hanging around the dungeon anyway, but why was there a hellhound here? I might know it was a lone wolf, so to speak, that had sought refuge here in the dungeon, but the players would be left to speculate – “wait; don’t these things hang around fire giants? Are we strong enough for giants?!?” For me, as a DM, it was one of my favorite parts of the game to watch and listen as the players tried to figure out things like that…and maybe make a few mental notes for some future encounter based on their speculation, all based on the appearance of a wandering monster.

Nice post about wandering monsters.

Another reason for wandering monsters is to ** scare the players **. Scare in the sense of horror-movie scare; scare in the sense of “this is why we’re here.” Non-random monsters are a risk, but the convention of the game is that they also hold the potential of reward. Wandering monsters are unknown, unknowable danger that can appear at any time. I occasionally toss the ol’ “d6 of Doom” not to “speed things up” or anything, but because the mere sight of that thing bouncing across the table, whether it lands 6 or not, makes everybody react like a bunch of 13 year olds at a monster movie the first time Frankenstein’s Monster shows up.

That kind of “scare” is part of the point of the game.

@Michael Monard:

Well, for 4e, WotC has set specific targets (->DC) for checks depending on

a) the level of the players and

b) how hard it is supposed to be.

If you say “a child could do that”, you set that as an easy DC. If it is improbable, it’s hard, else it is “medium”.

So the player rolls a d20 with his ability modifyer against that target. If he is over it -> success, else -> fail.

So, basically, I said: ok, roll a d20, if it is over some (high) amount, you catch yourself, else you fall 😀

Well, that would be appropriate for something important, but this wasn’t.

I am rather astounded at the “walking off a cliff” reference. Paul’s character did a comic pratfall and took one point of damage. Hardly “walking off a cliff.”

[…] something like this, I like the idea of old school style play – someone at the table has to map the dungeon as the party moves along. This way, the group has to positively identify their path through (and […]

I loved this adventure the first time we participated! The second time? It was no longer “unknown,” so I threw the damn thing away.

😉